5-10-5: John Pastoriza-Piñol, botanical illustrator

John and I were introduced through a mutual acquaintance when I was living in Australia. Funnily enough I first saw his work exhibited at the RHS London Flower Show a few years ago prior to our meeting. We bonded over our love of the arts and plants, and even caught up during his trips to United States. John has exhibited widely throughout Australia and internationally, including New York and Pittsburgh, Kew and London and Berlin and Madrid and has received numerous awards for botanical art including the American Society of Botanical Art Dianne Bouchier Award for Excellence in 2013. It's no easy feat to fulfill these artistic obligations while holding down a daytime full-time job in Melbourne, Australia!

Please introduce yourself.

John Pastoriza-Piñol, botanical illustrator

The arts or horticulture?

Both, can’t decide.

How did you parlay your scientific background into a career as a botanical illustrator?

When my interest in plants and gardening led to study botany at Uni, I was given the opportunity to travel to the University of Vigo in Galicia, Spain to complete my doctorate course. I studied the environmental impact of Eucalyptus globulus subsp. globulus in agroecosystems in northwest Spain. This tree, the Tasmanian Blue Gum, is native to Australia and been naturalized widely, including to Galicia. When I returned to Australia, I began studying botanical illustration with the renowned Jenny Phillips and haven’t looked back since.

Botanical illustration is a scientific discipline that portrays accurately the minute details of the plants. For clarity and simplicity, the plants are set against stark negative space, leaving little room to improvise. I can only think of Marianne North and Raymond Booth whose work went to incorporate the subject's habitats and Robert Thorton who took stylistic liberties to convey a romantic mood in the Temple of Flora. How do you surf between scientific precision and your personal creative touch?

The centuries-old art form of botanical illustration is highly specialised - where plant portraits combine finely observed detail with artistic expression. Today, botanical art is experiencing a resurgence of interest, and artists are adopting more contemporary interpretations, pushing the boundaries. Rich luminous hues and gorgeously exotic and rare botanical specimens define my work, however these are more than mere flower paintings. Closer inspection unearths a certain ambiguity of form and intent towards a dark and complex narrative. The familiarity and pleasure we derive from looking at a depiction of a beautiful plant or flower is somewhat challenged, and I like to urge viewers to look beyond the aesthetic and move into slightly more uneasy territory. While I want to encourage an appreciation for contemporary botanical art and accurate realism, I tend to aim for an exploratory narrative in my choice and composition of subject matter – the unusual and macabre always fascinate me.

Given your full-time daytime job as a college administrator, how do you set aside blocks of time to devote to painting?

I have been teaching intermediate/advanced classes at the Geelong Botanic Gardens since 2005 and I have expanded my teaching circuit to include interstate and international Master Classes, educating my unique approach to the art form. In addition, I have a “day job” at RMIT, a university of technology and design, as coordinator industry Engagement and Events for the college of business, which allows me to use the other hemisphere of my brain! This leaves me with little time to devote to painting but I manage to fit it in.

How do you cajole the horticulturists into giving you the rare plants to paint? It's hard to part with a rare or unusual plant one has devoted to propagating and growing.

My primarily focus is rare and unusual plants. Re-introducing less commonplace plants and unusual species certainly engages the audience. I find if you ask nicely and you most often you get the whole plant not just the bloom! Most plantsmen are very proud to have their treasure immortalised as a piece of fine art.

Watercolor is the primary medium through which plants are depicted in botanical illustration. There is no doubting its ability to impart a special translucence or 'liveliness' to plants. Have you explored other media besides watercolor?

Not as yet, I would love to work with glass, maybe in my retirement.

What are your current projects you're working on?

I am in the process of finalising a new series of works to be exhibited at a show titled (Vignettes: Prefatory, Empirical, Mimesis, Brevity) in 2015 at the Art Gallery of Ballarat. The Art Gallery of Ballarat was established in 1884 and is the oldest and largest gallery in regional Australia.

The exhibition is based on the concept of a vignette, which originally was used to describe a small decorative design or small illustration used on the title page of a book or at the beginning or end of a chapter. These small, pleasing pictures or views would have no definite line at the border and often the design would be a small, graceful literary sketch.

My component, titled Brevity, is based on the French proverb à la Chandeleur, l’hiver se passe ou prend vigueur (winter either wanes or gains strength). This part of the exhibition precariously balances several disparate components of botanical documentation and constructed social identity. The literal and subversive elements coexist uneasily on the same plane, while the rendering remains true to the fundamental principle of objective observation of the natural world.

The obvious harbingers of autumn invoke feelings of reflection, melancholy of the transience of life. The careful choice in thickness of each vellum skin is pivotal to the overall narrative, where the thinner clearer skins denote youthfulness and the thicker skins represent growing older and the aging of the body. The underlying tattoos which emerge from beneath the vellum are instantly recognisable to those familiar with members of certain subcultures. These strangers are identifiable by these visible markers and exercise our curiosity in discovering their ‘story’ – often the justification behind the tattoos.

The entire work is presented as a timeline or chapters from a book starting at late summer to late autumn. The fidelity of the underlying tattoo diminishes as if discarding of the troubles of daily life and suffering of the world. The familiarity and pleasure we derive from looking at a depiction of these images are somewhat challenged. Does the tattoo destroy the beauty of the work or do we learn appreciate its symbolism? They suggestively urge the viewer to look beyond the aesthetic and move into a deeper understanding about the reality of life, the choices we make and in the scars we take to the end.

What has been the public reaction towards your work in various exhibitions?

Botanical art has been described as the meeting place between the arts and the sciences; however, many contemporary art practitioners describe the genre as ‘pure documentation devoid of any social context’ and therefore not considered as an art form. Contrary to critique, we are witnessing an increasing interest in botanic art with artists and illustrators continuing the centuries-old tradition of accurately and artistically recording plants.

Surprisingly there is a resurgence of realism in contemporary art practice which has inspired many prominent artists to adopt more contemporary interpretations and therefore pushing the boundaries of this art form into mainstream. More established galleries are showing interest in displaying this art, and subsequently there are more opportunities to study and appreciate botanic art.

My works are designed to engage with the audience on an intimate level. In terms of the subject matter, the viewer’s experience is highly subjective and personal as they stimulates curiosity and allows the viewer to more engaged with each work/ group of works and can interpret in their own way bringing into focus the everyday.

What are some of your favorite influences (travel, fashion, etc)?

I do follow fashion and travel often yet these don’t exclusively influence my work.

You spend an inordinate amount of time teaching botanical illustration nationally and internationally. What are the challenges you face in explaining some of the techniques in botanical illustration?

Obviously with the medium of watercolour, patience and time are common challenges. Accuracy is vital, as the smallest exclusion of an integral plant structure may result in an incorrect identification. One of the downsides to this art form is that we are very critical on detail. If a work is not as detailed or as accurate, most viewers are shy to praise and quick to criticise. You must be thick skinned to deal with critique. The flower is always the first component to be completed as nature waits for no man and is always the first part to change/ deteriorate first. The foliage and bulbs/ root structure can take time as these do change too much.

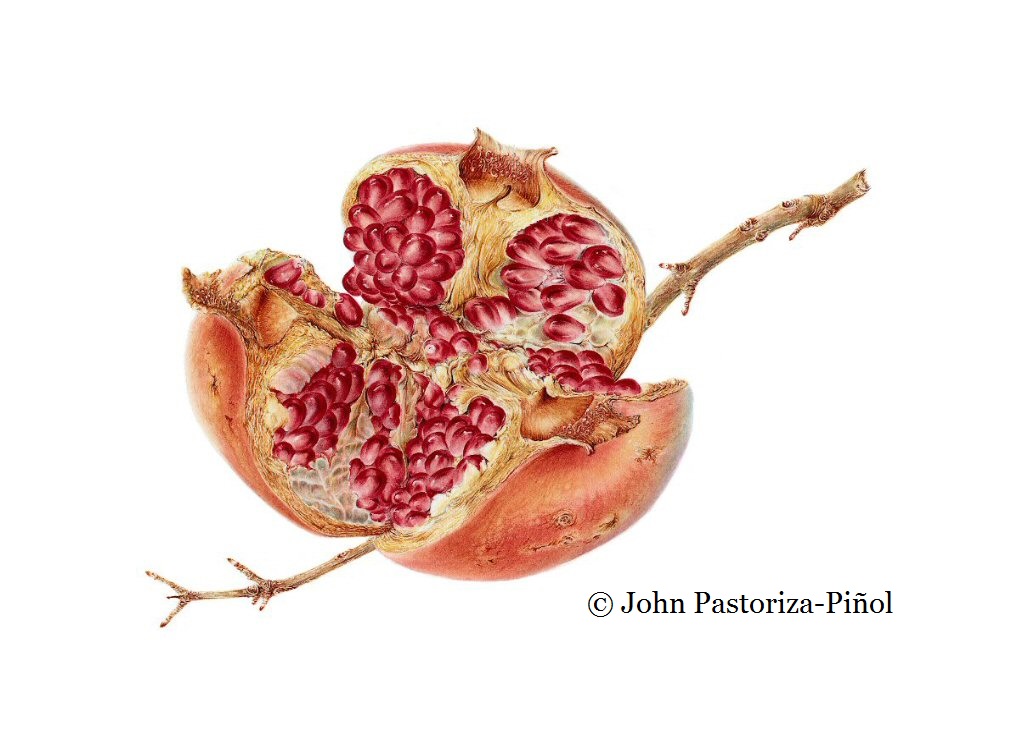

You seem to favor the pomegranate as a favorite subject for pupils to paint. Why is this fruit a chosen one?

Punica granatum L., pomegranate, is an ancient, mystical, unique fruit borne on a small, long-living tree which is native to the region of Persia and the western Himalayan range, and is now cultivated throughout the Mediterranean region and elsewhere. Pomegranates are considered an emblem of fertility and fecundity, and have a strong affiliation to women. The pomegranate features prominently in myth and religion as a symbol of the seasons of death and rebirth.

If you were marooned on an island, what would be your desert island plant to paint or grow?

I hope that never happens! Most of the plants I like wouldn’t grow there!

Do you have any favorite gardens?

Sissinghurst, Kent UK; Cloudehill, Melbourne; the private garden of plantsman Otto Fauser.

Any advice for anyone interested in exploring botanical illustration as a career?

I have been a member of ASBA since 2005/2006. The ASBA is the benchmark on which all botanical societies should be based. The running of the society, and the cohesion of both chapters and international artists is extremely well managed. The annual conference is truly a highlight, bringing together artists from around the US and abroad. It is wonderful to be able to present your work on an international platform. ASBA is at this stage the most global society of artists, that is until the creation of the International Society of Botanical Artists!

Thank you John!