Summertime Reading

If you're an experienced gardener like ourselves, chances are that you may have purged your horticultural library of books that are visually arresting, but offer little way of substance. One may argue that it is impossible to have too many gardening books - although I disagree about holding on some titles. After going through a phase of English-garden mania, I've given away or donated several books long on garden photography, but short on practicality (the maritime English climate is a different creature than that of the Northeast climate). You can only gaze lovingly at those lush Edwardian herbaceous borders, crumbling aged brick walls, and moss-encrusted statuary before you realize that time, money, and history is finite on your own grounds. However, a few do leap over that 'garden fantasy' realm to provide erudite commentaries on regional gardening styles or just pulsate with the gardener's personality that the photography and text collude together perfectly.

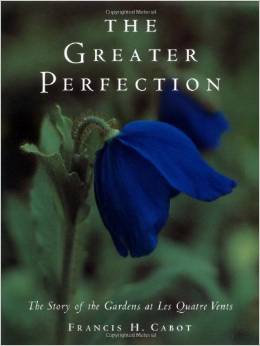

The late Frank Cabot created a magnificent garden, Les Quatre Vents, in the chilly reaches of Charlevoix County, Quebec, Canada, which he fortunately wrote about its creation in The Greater Perfection: The Story of the Gardens at Les Quatre Vents. At first impression, the garden appears to be a pastiche of different garden styles poached from England, Japan, China, and India, but studied closely, become something different as interpreted through Cabot's vision. The Palissades, with its double row of lindens underplanted with spring bulbs, bear a passing resemblance to that of the Lime Walk at Sissinghurst, except for its mirrors at both ends to give an illusion of infinity and its diagonally split square paved pathway lifted from Tintinhull. A photograph of an arch designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens for the Royal Mughal Gardens in New Delhi, India, motivated Cabot to commission and erect a version to frame the view of the Laurentian Mountains, and the swinging bridge through the Ravine took root of an idea during a visit to Wakehurst Place, the country satellite of Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Cabot is not only a skilled visionary of spaces and structures, but also a sharp-eyed plantsman whose interests range from alpines to delphiniums, which tower to legendary spires in cool climates. We gardeners in more southerly locales can only envy the Himalayan blue poppies and primroses that have become flourishing colonies at Les Quatre Vents. However, failures do bedevil Cabot who details the ups and downs of choreographing herbaceous perennials for optimal display, or his horrified reaction at the Arch's sudden collapse from rot and tree roots. His honest tone is ever more enthusiastic, a change from the manicured perfection of the writer's voice in other glossy garden tomes. Sometimes the voice of an external observer is necessary for a realistic appraisal of a garden as Tony Lord demonstrates in Gardening at Sissinghurst.

No seasoned garden tourist leaves Sissinghurst without a lasting impression, even if some have harped about its institutional, 'fossilized' feel and the loss of Vita Sackville West's disheveled, romantic atmosphere tamed by her partner Harold Nicholson's Italianate axes. Its magic was not lost on me during my first visit - as I climbed the spiral staircase to the top of the Elizabethan tower for stunning views of the garden and the surrounding Kentish Weald, I imagined Vita herself clambering upside, retreating into the writer's alcove with its windows flung open on a still English evening. There she may have penned the following: “All the same, I cannot help hoping that the great ghostly barn-owl will sweep silently across a pale garden, next summer, in the twilight – the pale garden that I am now planting, under the first flakes of snow” (In Your Garden). Dwarfed by the yew hedges, I felt childish stirrings, flung open only by that elusive quality of mystery we gardeners endlessly and hopelessly attempt to nail. The borders were all billowing with all manners of shrubs, vines, herbaceous perennials, and bulbs. For those unable to experience Sissinghurst, Tony Lord's Gardening at Sissinghurst (Frances Lincoln 2000) comes closest for its sumptuous photography, enlightening and well-penned chapters on each specific gardens, and the behind-the-scenes eavesdropping. Lord himself is a photographer and a horticultural taxonomist whose expertise once extended to editing yearly the RHS Plant Finder, the horticultural Yellow Pages. His prose moves fluidly between horticultural and botanical terminology and the garden's narrative. Importantly Lord gives overdue recognition to the late Pam Schwerdt and Sibylle Kreutzberger, the two female head gardeners who elevated the art of planting at Sissinghurst during Harold and Vita's tenure.

The trans-Atlantic horticultural love affair does not start or end with Sissinghurst as Andrea Wulf's Founding Gardeners: The Revolutionary Generation, Nature, and Shaping of the American Nation (2010) and The Brother Gardeners: A Generation of Gentlemen Naturalists and the Birth of an Obsession (2010) both convey the beginnings of American's horticultural heritage and the English fad for North American plants. Thomas Jefferson, considered the father of American agriculture and horticulture, visited English gardens, which certainly influenced his estate at Monticello. The English landscape movement was partly reliant on North American trees and shrubs to fulfill that ideal 'Arcadian' idyllic. Although the subject matter may seem dry, Wulf keeps the pace moving without becoming bogged down by factual details or historical arcs and the personalities involved are fully drawn out, not hastily sketched caricatures.

What new books will land on my summer list this year? As I peruse the farmers' market groaning with local summer produce, I hope to read Dan Barber's The Third Plate (2014). Barber runs the Blue Hill restaurant, the Northeast's answer to Alice Waters' Chez Panisse in California, in rural New York, and is perfectly positioned to elucidate his views on the American cuisine and food production. Barber recently published a compelling editorial 'What Farm-to-Table Got Wrong' (http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/18/opinion/sunday/what-farm-to-table-got-wrong.html?_r=0) calling for consumers to support lesser known crops, such farro (emmer wheat), cowpeas, and mustard greens, eclipsed by asparagus, strawberries, peaches, and tomatoes, the equivalent of 'charismatic megafauna' in the farm-to-table movement. The editorial, certainly a subset of The Third Plate, had me curious to read more on what Barber will write. I always wanted a summer holiday in Italy (having limoncello on the Amalfi Coast wouldn't hurt), a desire that will only grow with Helena Attlee's The Land Where Lemons Grow: The Story of Italy and Its Citrus Fruit (2014). A resident of Italy for 30 years, Attlee has written four books about Italian gardens and her background should serve her well in her focus on the Italian obsession with citrus. The Land Where Lemons Grow should satiate the culinary-curious as well as the botanically-inclined. Both books will enhance my usual diet of magazines and weekend newspapers, and leafing through pages rather than the glow screens of IPad or Kindle is a soothing ritual.