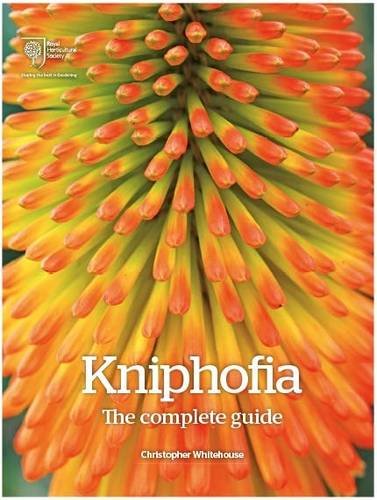

Book Review: Kniphofia: the complete guide by Christopher Whitehouse

by Eric Hsu

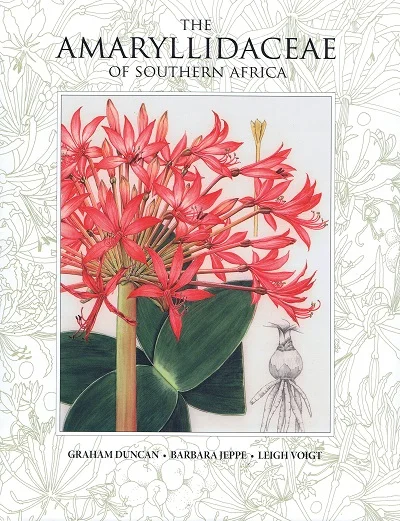

One outcome of the European colonization in South Africa was the establishment of botanic gardens and the affiliated research centers. Today Kirstenbosch National Botanic Garden can trace its founding back to 1913 when a British expatriate Henry Harold Pearson, who had moved down in 1903 to chair the botany department at South African College (University of Cape Town), agreed to serve as its first director in spite of difficult beginnings. Botanists wasted no time in documenting the floral biodiversity of South Africa by publishing their finds and preserving specimens in herbaria like the Compton Herbarium. Books were published as people clamored to learn more about the exotic flora, some of which was then dispersed to other parts of the world (with some disastrous ecological consequences). These books followed the European tradition of commissioning skilled botanical illustrators to produce watercolor paintings and having botanists prepare the scientific descriptions.

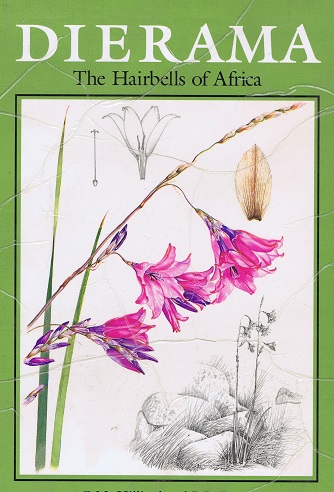

A treasured plant monograph in my library is The Genus Dierama by O.M. Hilliard and B.L. Burtt, which I was fortunate to purchase from the RHS Wisley Bookshop despite being out of print! The watercolor renderings and pencil sketches of these photogenic iris relatives by Auriol Batten are among the best in the South African botanical illustration. Dierama, better known as Venus's fishing rods, are best in mild maritime climates, such those of Ireland, northern California, and United Kingdom. They were in full glory when I interned in plant records at Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, and some were actually type plants from which Hilliard and Burtt described new species. Another plant monograph The Proteas of Southern Africa by John Rourke follows the same format with illustrations by Fay Anderson. I am often reminded of my days in Australia when I would buy cut protea flowers for floral arrangements. A local grower would arrive at the weekend market with buckets of different proteas to sell, and sometimes the temptation was too much to leave without them. Months later, I found myself transplanting Protea cynaroides, rightly called the king protea for its majestic large flowers, in a friend's garden.

Kniphofias always drew snickers from my non-gardening friends who knew them as red hot pokers for they saw bawdry humor instead. However, I wasn't always appreciative of what these South African natives had to offer. I first knew kniphofias as tritoma when I purchased plants from the bargain table, and watched them thrive in my modest garden plot. Unfortunately their lanky foliage always looked unkempt and became a liability as the flowers faded quickly in summer heat. Frustrated one day, I pulled out the plants to create space for more desirable perennials. Christopher Whitehouse's horticultural monograph on Kniphofia, the first to be published in the RHS's five year long horticultural taxonomy project, may change my perception for the genus. Christopher was the Keeper of Royal Horticultural Society Herbarium when he was one of my advisors on my M.S. project on putative Erica hybrids. I was aware of his life long affection for South Africa flora especially when he had worked on his doctorate on Cape roses (Cliffortia) in Cape Town. The Royal Horticultural Society Botany Department would not have found a more qualified person to study and publish the Kniphofia monograph, and the last authoritative reference was in the botanical journal Bothalia. Sorting out the species is already a monumental task, and adding the hybrids and various cultivars turns into a slippery path because Kniphofia interbreeds easily.

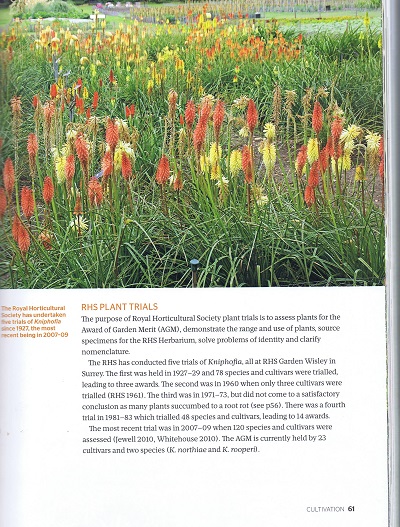

Whitehouse was able to draw from the RHS Plant Trial of kniphofias to sort out nomenclatural issues and confusion in the trade; the results compiled with the help of the RHS Herbaceous Plant Committee and RHS Botany Department resolved some contention over cultivars. He has had the good fortune and perspicuity to conduct field studies of the genus in the wild. Bringing together the cultivated plant nomenclature and field studies gave a better understanding of the polymorphic genus.

Throughout the book, one will find useful charts that categorize information, like the chronology of naming for various Kniphofia species, introduction of cultivars especially those raised by Maximilian Leichtlin, or the endemic species by geographic region. Gardeners will find the flowering period of the species and the color grouping of cultivars indispensable for planning their plantings.Most books on specific genera lack such charts that help readers make good decisions about plant selection.

The chapter on relatives helps elucidate the relationship of Kniphofia to similarly confused genera (i.e. Aloe and Bulbinella) in the same family Asphodelaceae. Whitehouse points out that traits separate Aloe from Kniphofia in the former's succulent nature, absent keel in leaves, and upward orientation of the floral pedicels (stalks connecting the flowers to main stem). However, Aloe and Kniphofia show ecological convergence in their tubular flowers, which are adapted for pollination by sun birds, although competition is avoided by different flowering seasons (Aloe dominantly winter). An interesting note is that kniphofias with V-shaped leaves are less likely to flop than those with less pronounced V-shaped ones. It is a diagnostic feature worth remembering for anyone who has had the unpleasant task of cleaning slimy, cold damaged leaves in spring. One thing that surprised me was the medicinal use of Kniphofia for female ailments, although their use for twine and threaded talisman necklaces seem expected.

Cultivation is not shortchanged here as it would be in other monographs. Readers need to be aware that the perspective is that of UK rather than other regions which would experience either warmer summers or colder winters. Waterlogged soil during winter is usually the chief demise of kniphofias in northern climates, hence drainage is usually recommended. However, some moisture is needed if plants are to grow and produce good flowering.

The remaining 2/3 of the book is given over to species and cultivars. Whitehouse has mercifully pared down the diagnostic descriptions in floras to those important for identifying the species in an accessible manner. Each species is prefaced by color photographs that depict the flowerhead, the plant in full habit, and the habitat. Additional comments are reserved below the bullet list of traits. Whitehouse follows with the chapter on cultivars. Organized by color, cultivars are condensed with short descriptions with the breeder, date of introduction, and dimensions. A checklist of epithets helps with cross-referencing correct names and their earliest discovered sources. With several hundred varieties in existence, a gardener can find sorting out the names a time consuming ordeal. The checklist does much to straighten out the nomenclature affair.

Conclusions drawn in Kniphofia are not necessarily firm. A nurseryman friend who breeds kniphofias contends that Kniphofia thomsonii var. thomsonii 'Stern's Trip' is not sterile, although it is not overly fertile. He has grown a few plants from its seed, despite the progeny not having any appreciable ornamental value. Another nurseryman has likewise raised seedlings, one of which is currently evaluated for its ornamental quality. However, no disagreement will and should dissuade gardeners from seeking out Kniphofia as a reference. It is rare for books to bridge the gap between horticulture and botany.